Lenne Klingaman

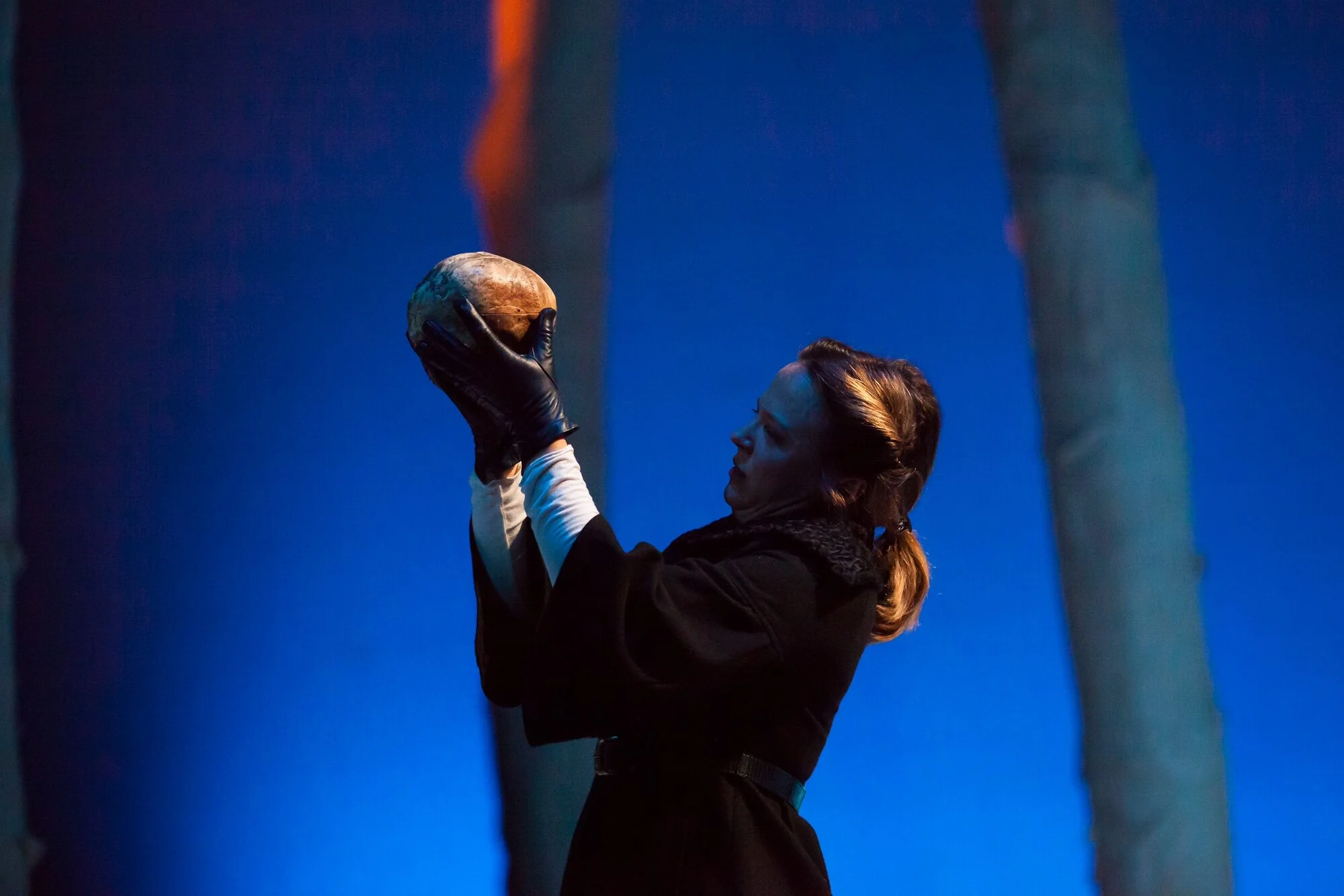

From a deft turn as Hamlet with Colorado Shakespeare Festival to a standout Broadway run as the compulsive and shy Dawn in the musical Waitress, Lenne Klingaman is an actor of great depth and range — subtle, funny and always surprising.

When 2020 began, Klingaman was fresh off a world premiere of Will Eno’s The Underlying Chris at Second Stage. Then COVID came and the performing arts ground to a halt. She and her husband retreated to her family home in Minnesota for the summer to regroup, and Lenne found herself in her childhood bedroom asking herself, “Who was that kid who sat in front of that mirror and made faces and made up stories and practice weird comedic bits? Where did that come from? Why was I drawn to this?”

““It’s not talked about, and we just can go away and try to become invisible. And I feel like art is one of those places that tells those stories and makes things visible that have not been.””

“It's been an interesting battle of the soul, in terms of the career and just everything,” Klingaman says of the great COVID theatre pause. “I think we're all processing it in so many different ways … for me specifically, it was really stopping the perpetual forward motion and kind of linear approach to a career. ‘You do this, and you're bad if you don't do this, and oh, no, I'm not getting this.’ And, you know, that kind of ladder. And so to just have it all be taken away. It's like, what's left? And why did I do? Why do I want to do this in the first place?”

Being on the threshold of a serious New York theatre career when Coronavirus comes knocking while also participating in the other challenges of 2020, from electoral politics to the fight for racial equity, is enough to make anyone stop and take stock.

“I can really say in this moment, that there's something that's that I'm kind of thankful for, in a weird way,” she explains. “It stopped me in my tracks in terms of taking care of me, both in a self care way but also as an artist and the question of ‘what do you want to make?’”

It’s important to note that this was Klingaman’s second major career pause in just two years. “I lost a pregnancy,” she explains. “And it was, weirdly, almost at the same time, the year prior — so 2019. A big halt, and a big stopping in my tracks.”

That event was the end of her stint in Waitress, which had begun with creating the role of Dawn for the national tour and ended on Broadway.

“I don't think I've always been modeled by our society on how best to take care of yourself … especially [with] women's health,” Klingaman says. “It's not talked about, and we just can go away and try to become invisible. And I feel like art is one of those places that tells those stories and makes things visible that have not been. I know, having gone through some things that are have been made invisible in our society — like pregnancy loss, abortion, things like that, especially if it's to protect the mother — when I see art decide to confront those things, even just in telling the story … you feel seen and you feel part of something, feel part of the collective.”

For all workers in the performing arts, the pandemic has taken an integral part of that collective feeling away. The electric relationship between performer and audience, the community that the creation of a live show creates, the mutual communion between so many people — it has all been diminished, and we have no clear sign of when we can return to it in any viable form.

“Having that be one of one of the pulsing heartbeats of a city just coming to a complete halt, when it's also your own pulsing heartbeat, it's really hard,” Klingaman says. “You had to kind of navigate what that is in you, what causes that pulse went went to that heartbeat, you know what I mean?”

Klingaman ultimately found that, for her, that pulse comes from storytelling in all its forms, and the connections it makes between people. For her, that included returning to music outside the theatre realm. In 2015, she released a vocal album of originals and covers of artists including Leonard Cohen and her father, songwriter Steve Klingaman. The 2020 pause gave her the opportunity to continue work on a followup record.

Inward journeys, done well, eventually turn outward once again, finding the places where personal work can connect with others and create better, more just community.

“I think especially with this election, the thing that keeps coming in is empathy and equality, empathy and equality,” she says. “It’s become this sort of mantra of mine when I feel like there's something more I should be doing, when I feel like I'm about to lose it because I can't do anything more … That’s what I keep coming back to, and the way that this this career — and I include music and stage and film and all that in it —puts you in someone else's shoes and your job is to try to understand them and try to be them, and tell their story and practice and stretch the muscle of empathy.”

This combination of empathy, equality and visibility are the goals of Klingaman’s storytelling drive, and they’re goals she intends to achieve through any and every creative avenue, whether it’s a musical, Shakespeare, film or songwriting.

“There are so many ripple effects to being human in this time,” she says. “And I think I art can help us see ourselves and things that we didn't even know we were making invisible… visible again.”