Tasneem & Yemurai Tewogbola, Part 2: The Art of Conversation

The Art of Conversation

This is the second of a two-part feature on Tasneem and Yemurai Tewogbola. Tasneem is a writer, storyteller, activist, former journalist and associate director at Nashville Public Library. Her daughter Yemurai is a 17-year-old high school senior planning to study interior design. This installment focuses on the art of conversation and the role of the artist in the present moment. Don’t miss Part 1, where we talk about Act Like a GRRRL.

“I believe I was raised to be a writer.” Tasneem Tewogbola was set on her path by a driven mother who engaged her five children in writing, public speaking and performance early, always pushing them to develop their curiosity and individual voice.“I call her the Mo’ Better Mama,” Tasneem laughs. “You can show her anything, and she’ll upgrade it.”

With four daughters of her own, Tasneem continues the tradition, cultivating a deep and direct tradition of conversation in the family. It’s something that 17-year-old daughter Yemurai finds as comforting as it is challenging. “The people that I'm comfortable with, the people that I live with, are now okay with me expressing my emotions,” she says. “We feel like this is the safe space created for us, and I feel like that’s really something to value during this time.”

“I think that we have be a little bit slow to self-congratulate. And I think we need to spend some time in self-examination. I would love to see what art comes from that.” —Tasneem Tewogbola

With careers as a journalist, writer, storyteller and associate director at the Nashville Library where she develops dialogue-heavy workshops like Civil Rights & Civil Society, Tasneem’s work is both soulful and penetrating, exploring the places where the personal, familial and communal intersect, and the fluorishing and friction that come from their meeting.

To be successful at any of this work, an artist must possess innate curiosity and a talent for close, empathetic listening. “I really do consider it an art and science, the conversation,” Tasneem says. “It begins with the curiosity. But also at a certain point, I started to think, ‘who else can I tell you know where can I share this?’ How can I write this down? Why am I meeting this person at this time?’”

It’s an art that Tasneem brought into her family, and that she gave great attention to as the summer of 2020 grew in intensity. “I'm having these conversations with the girls quite intentionally about identity, the identity that they have as black women, as black girls,” she explains. “We’re sitting down and having a conversation. What are we all fighting for? You know, what is this idea of resistance, and what are we resisting? What does the word brutality mean? What do you like about being black?”

“The best way I know for me to access that in my girls, whose ages are 17, 14, 12 and nine, is to enforce the art of conversation,” she adds. “My goal is that they begin to ask themselves those questions, ‘why are we doing what we’re doing?’ … to actually start to think, ‘what is my personal connection to this and what’s my personal responsibility?’”

Anyone with experience with teenagers (or just remembers what being a teenager was like), might be skeptical about how a young person might respond to such focused introspection and the expectation to share it. But Yemurai finds it both comforting and empowering. She’s able to ask her parents hard questions, and knows that they’re ok with it. “They’re ok with me coming up with weird questions or asking them why they're doing something, not necessarily to try to say they're wrong, but just to understand them better and also understand yourself more,” she says. “It's really about: do you feel comfortable around the people that you actually have to live with?”

“And sometimes, the answer is ‘no.’” Tasneem adds. “I think discomfort is a part of this art we're talking about … The practice has to do with wading through the discomfort. When the answer to certain questions is ‘maybe I'm not involved because I don't care.’ Maybe many of us aren't involved in things because we don't care. And then let's investigate that. What does it mean to not care?”

With America near to boiling over with the need for major change, this is a crucial point. Tasneem and Yemurai repeatedly touch on the need for deep introspection and empathy alongside action.

“Let's also investigate this hierarchy, I call it the hierarchy of revolution,” Tasneem says. “We think that to be an activist, you must do these things. You know, ‘did you go to the March?’ You didn't go. You know, or ‘do you have a Black Lives Matter banner in your yard?’ Or if it's voting time, ‘do you have the I Voted sticker on?’ All these different ways to create identities when in fact, I think there's several other layers that count. So we get to as artists, decide what our activism looks like, and to also not judge and hold each other sort of emotionally hostage if it doesn't look the same for everybody.”

Yemurai adds,“Now you feel the need to post this petition that you didn't sign yourself, that you're posting so nobody says that you didn't say anything. [I need to be] more self-aware of why am I actually doing it. And even if I don't do it, does that mean I don't care … our lives are so fixed on social media that if you're not reaching out, if you're not posting this thing, you're not active. Not true. Some people just don't want to post for now.”

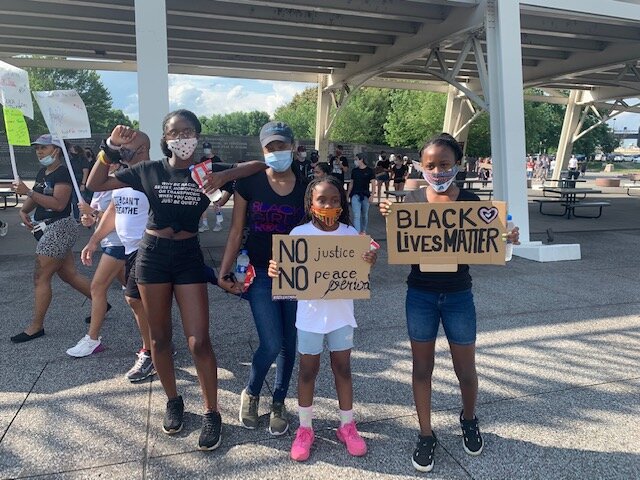

Tasneem and family did this deep work before joining recent Nashville marches, to evaluate not only their personal motives for being there, but also how their voices can effectively advocate for change.

Conversation and social justice inextricably linked, and both are tools for creation. Tasneem and Yemurai are curious to see where this moment takes art.

“I know this is where great art is made,” Tasneem says. “When I think of myself as a student of revolution, I think of myself as a student of the human quest for liberation. So where are people trying to get free, and what are they trying to free from? And what I have to admit is that, as I think about the historical timeline that lends itself to the awareness of people fighting in Cambodia or Iraq or Syria, or Burkina Faso or Madison, Tennessee, is that people are taking all of that rage and anger and frustration and still being able to access joy, which then informs the art, which to me is the magic.”

“People are recognizing they're actually a part of history,” Yemurai says. “We’re in a pandemic, it's protesting, it’s political systems falling down and finally being exposed, things like that. More awareness of ‘what exactly are we okay with during this time?’”

“Will the summer of 2020 be the jump-off for something that feels tangibly amazing?” Tasneem asks. “And so I think conversation is part of it, but right back to self-introspection. What about the other marches I didn't march in? The other times I saw people suffering and I thought, ‘hmm, is The Voice on?’ And I turn the channel. I think that we have be a little bit slow to self-congratulate. And I think we need to spend some time in self-examination. I would love to see what art comes from that.”

Don’t miss part one of our interview!

LEARN MORE:

Tasneem and Andrea Blackman’s Civic Engagement at the Nashville Public Library

This amazing video of Tasneem